In an age where algorithms know us better than our loved ones and virtual lives carry more weight than physical ones, Black Mirror feels less like science fiction and more like prophecy. Since its debut in 2011, Charlie Brooker’s anthology series has captured a particular kind of 21st-century dread: the kind that stares back at us from smartphone screens and surveillance feeds. But Black Mirror didn’t arrive in a vacuum. It’s part of a long tradition of television that dared to tell standalone parables about morality, mortality, and the monstrous. From the eerie fables of The Twilight Zone to the ghoulish humor of Tales from the Crypt, the anthology format has always been a haunted house for cultural anxieties. And Black Mirror, with its sleek, digital horror, may be the format’s most chilling room yet.

A Legacy of Parables: Black Mirror’s Predecessors

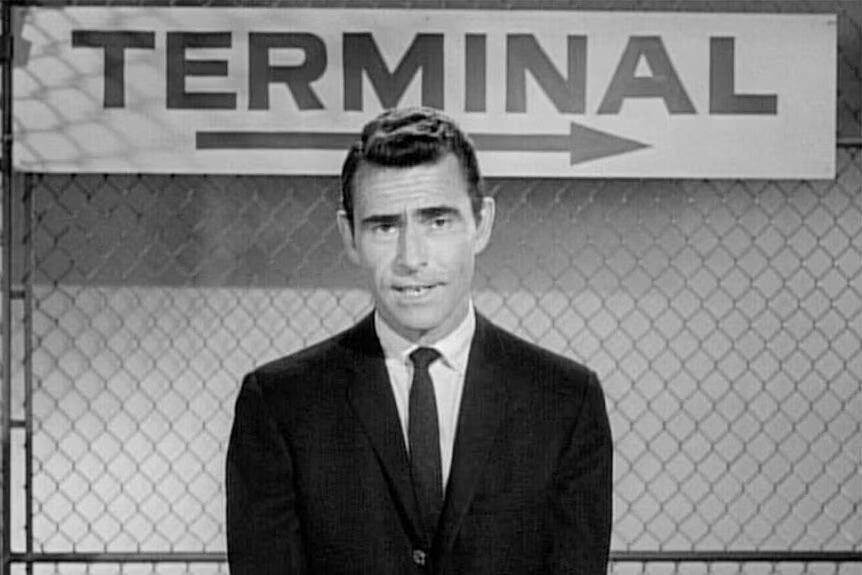

The anthology format has long served as a vehicle for speculative storytelling that confronts societal fears. Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone (1959) set the gold standard, delivering concise moral tales steeped in Cold War paranoia, existential dread, and often, a supernatural twist. Its stories used sci-fi and fantasy to explore deeply human dilemmas, prejudice, authoritarianism, and the fragility of identity. As Serling himself put it, “I wanted to write reflective essays on human behavior, but people would only watch them if they came with monsters.”

In the 1960s, The Outer Limits leaned further into high-concept science fiction, offering tales of alien encounters, body horror, and technology gone awry. It posed questions not just about human nature but about our place in the cosmos. Shows like Tales from the Darkside (1983) and Tales from the Crypt (1989) brought horror and dark comedy into the fold, trading the moral gravity of earlier anthologies for ironic punishment and pulp-style shocks.

These series shaped the landscape Black Mirror would inherit: the single-episode format, the surprise endings, the often bleak commentary on human weakness. But while past episodes often invoked ghosts, aliens, and monsters, Black Mirror trades in a different kind of terror, one grounded in the all-too-real possibilities of our digital future.

Modern Mirror: What Sets Black Mirror Apart

Black Mirror distinguishes itself by removing the veil of the fantastical. There are no haunted houses, no intergalactic wars. The horror is plausibly close: an app that ranks your social status (Nosedive), contact lenses that record everything you see (The Entire History of You), robotic bees turned weapons (Hated in the Nation).

What elevates the show is Brooker’s deft mix of cynicism, satire, and psychological realism. Many of the show’s episodes aren’t cautionary tales in the traditional sense. Technology isn’t inherently evil; it reflects how easily we misuse it—or how systems magnify our worst instincts. Black Mirror asks: If we could do this, why shouldn’t we? And what would it mean if we did? As Brooker once said, “Each episode should be a different genre, but the common thread is that they’re all about the way we live now—and the way we might be living in 10 minutes if we’re clumsy.”

Unlike its predecessors, Black Mirror is intensely personal. Episodes often hinge on relationships—romantic, familial, societal—and how they fracture under the strain of technological intrusion. The pain is not abstract. It’s intimate.

“We’re Already There”: Real-World Reflections

The eerie prescience of Black Mirror has been noted repeatedly. Nosedive foreshadowed the Chinese social credit system. The Waldo Moment eerily mirrored the rise of populist politics and meme-driven candidates. Be Right Back speaks to grief, AI, and the ethics of digital resurrection. These themes are now central to ongoing debates around machine learning, deepfakes, grief tech, and digital personhood.

The phrase “it’s like a Black Mirror episode” has entered the cultural lexicon, shorthand for unsettling technological developments that feel more like dystopian fiction than reality. This resonance has made the show more than entertainment. It’s become a framework through which we understand the present.

Madrid-based creative school brother ad has taken the we’re living in a black mirror episode meme and has turned it into a speculative ad, not related to Netflix

The Future of the Anthology Format

Thanks to Black Mirror‘s popularity, anthology storytelling has seen a modern revival. Shows like Love, Death + Robots, Inside No. 9, Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities, and even Jordan Peele’s reboot of The Twilight Zone owe part of their cultural relevance to the cultural appetite Black Mirror helped awaken, or perhaps reawaken.

However, as the show has aged, some critics argue that its impact has dulled. Later seasons have been accused of self-parody, or of falling behind real-world developments. It raises the question: can an anthology rooted in speculation keep up when the world is already a rolling dystopia?

Conclusion: Still Holding Up the Mirror

Black Mirror may not always hit with the urgency of its early episodes, but its core strength remains: it forces us to look. To question the assumptions we make about convenience, connection, and control. In carrying the torch from The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, it has redefined what speculative television can be in the digital age. Not just allegory, but autopsy.

The mirror it holds may be black, but it reflects our world all too clearly.

🕶️ What’s your favorite Black Mirror episode? Which one feels closest to real life? Drop your thoughts below or tag us @DJVampDaddy across platforms.

🦇 Want more retro-futurist dread? Subscribe to The Twilight Tone for fresh essays, reviews, and darkwave-drenched insights.